Review | Toward an ecological physics and a physical psychology

In this 1995 article we can find some of the expectations that the Gibsonian narrative had for the study of cognition in the current century. I find some of the ideas raised in this article fascinating and worth discussing.

Introduction

At the end of the last century a myriad of ideas surrounded the paradigm of cognition. On the one hand, there was the resurgence of structuralism through cognitivism, a perspective that interprets mental states as computational states. As a counterpart we find ecological realism, a perspective that, like 19th century psychological functionalism, studied the individual adaptability of cognitive traits under different contexts. In their article “Toward an ecological physics and a physical psychology”, the authors Michael Turvey and Robert E. Shaw offer us a rich compendium of unresolved problems and unfulfilled expectations for the 21st century regarding “knowing about” as a property that some material systems can possess with respect to themselves and to other material systems. When I scrutinized this paper I was able to find quite interesting aspects, presented below as a review, which I consider important for the development of modern cognitive science.

Avoiding Dualism

Dualism as we know it today can be traced back to the 17th century, when René Descartes characterized the mind as a non-physical substance. Close relatives of the mind-body dualism are symbol-matter dualism, subjective-objective dualism, and perception-action dualism. In any case, the logic followed is the same: two things referred to are defined independently of each other, studied independently of each other, and interpreted through independent scientific accounts. Thus, in trying to understand how the states or processes of both phenomena are connected, mysteries arise that may (or may not) be scientifically addressable.

In their article Turvey & Shaw point to the aforementioned dualisms as instances of organism-environment dualism. This generalization establishes that a theory of the organism (the “knower”) can be built independently of a theory of the environment (“the known”), and vice versa. In the words of the authors: “In our view, the most important conceptual step to be taken in the twenty first century, with respect to the foundations of a scientific attack on “knowing about,” is the rejection of organism-environment dualism and the acceptance of organism-environment mutuality and reciprocity”.

In support of their perspective, Turvey & Shaw draw on geological data showing that the increase in atmospheric oxygen over evolutionary time, due to the activity of living things, provided the potential required for progressively higher ordered states. With the above, the authors leave a clear message: “Living things and their surrounds are not logically independent of each other. Together, they constitute a unitary planetary system abiding by a single and directed evolutionary strategy that opportunistically produces—in progressively more varied and intense ways—the means for the global unit to generate entropy”.

Considering Affordances

In “The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception” James J. Gibson defined affordance as the potential for action that an environment offers to an organism based on its capabilities. This concept provides a description of the environment that was directly relevant when conducting behavior, describing the possible interactions between an individual and their surroundings. As pointed out by Turvey & Shaw, we usually think of the environment as fixed and neutral with respect to the organism and its actions. However, the concept of affordance uncovers the possibility of considering the environment-for-the-organism as dynamic and action oriented.

In order to put on the table a mathematical roadmap on which to formalize the concept of affordance, the authors define effectivity as the causal propensity for an organism to effect or bring about a particular action. As noted in the text, “whereas affordance is a disposition of the surrounding environment, an effectivity is the complementing disposition of the surrounding organism”. From this perspective an organism and its niche constitute two structures that relate in a special way such that understanding of one is, simultaneously, an understanding of the other.

The authors suggest that such a correlation can be well captured with the mathematical notion of duality, a correspondence between two entities that may belong to different categories. Turvey & Shaw’s message is clear: the environment is as dynamic as an organism, and as we shall see below, to understand this relational property it is possible to appeal to the concept of symmetry.

Developing New Physics

Throughout the text the authors suggest the necessity of developing new physics in order to unravel those conceptions of “knowing about” that were held at the end of the last century. Cognition is generally presented as a rational process of inference. However, Turvey & Shaw’s proposal is to assign controlled locomotion as a precursor of cognition. In the authors’ words: “understanding knowing about will demand both a broadening and an enrichment of the current understanding of ‘energy’ and ‘information,’ an appreciation of the confluence among all three intuitive ideas, and a physically grounded understanding of an even more inexact idea, namely, intention”.

With respect to that last concern, Turvey & Shaw suggest that the notion of Shannian information is useful to address the formally defined states of affairs of communication and representation, but not the physical states of affairs by which informed interactions might occur between an organism and its surroundings. Organism-environment interactions require information in the sense of information about something; that is, information of a kind that permits the perception of something rather than the discriminating among things.

Thus, by means of mass-energy-locomotion relationships, the authors conclude that “when properly understood, information and energy are reciprocal aspects of nature. This reciprocity is neither required nor revealed by a physics that considers natural systems that exhibit the quality of “knowing about” as special systems. The reciprocity is brought to the forefront only when systems exhibiting “knowing about” are understood as more general in respect to the principles that underlie them than the material systems currently addressed by physics”.

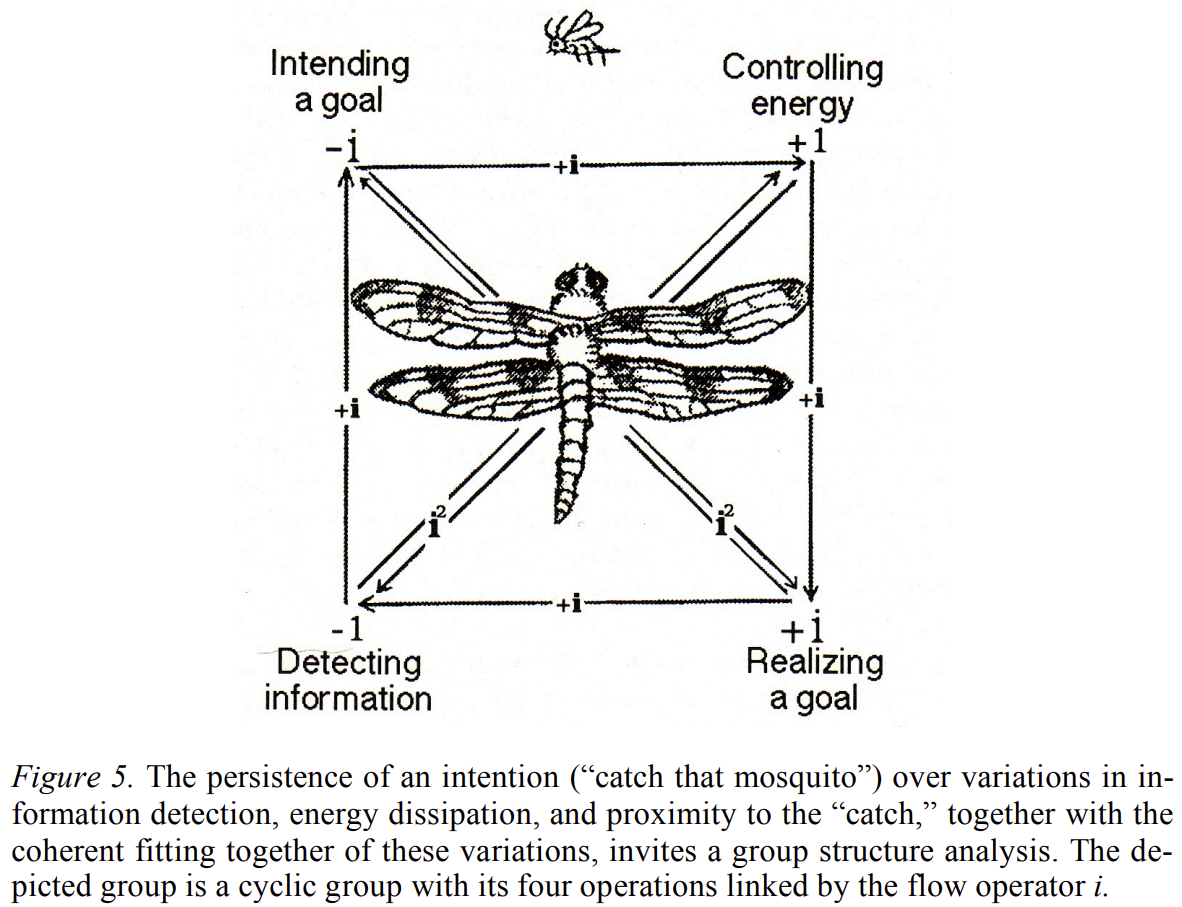

To conclude their paper Turvey & Shaw study intentional behavior as a symmetry of the ecological scale. The question is very simple: Can a group (in the mathematical sense) be defined that captures the minimal essential structure, the basic symmetry, of intentional behavior? And if so, what hidden structure is it likely to disclose? In response to this, the authors offer us a minimal symmetry group that allows us to study information detection, goal intention, energy control and goal realization in a unified way. For me this fact is super elegant, since it brings back the ultimate intellectual legacy bequeathed to contemporary and future scientists by Einstein: constraining experimentation and theory building by symmetries.

Figure 5 from the paper here reviewed.

Figure 5 from the paper here reviewed.

Conclusions

Let us recall that the suggestions described throughout the text date back to 1995. Today, after almost thirty years, we can ask ourselves how much progress we have made in this regard. In adopting the reciprocity between an organism and its environment, I could not help but think of the computational enactivism proposed by Korbak, which acknowledges and emphasizes active inference as a computational process (as opposed to only being describable as computing), while at the same time entailing a fully-fledged enactive theory of mind. Recently the concept of affordance has also been explored from category theory by Hirota et al. Their category-theoretic approach offers a potential solution to the problems and limitations associated with existing set theory-based frameworks for affordances, paving the way for a future theory that better accounts for the open-ended interplay between organisms and their environments.

Currently we also have several attempts to develop new physics that allow us to understand the phenomenon of cognition, or at least to capture the connection between energy and information. Some examples are Bayesian mechanics, assembly theory and irruption theory. Each of these instances breaks some of the conditions afforded to us by ecological physics. Bayesian mechanics rationalizes cognition as an inference process, which leaves out controlled locomotion as a fundamental part of “knowing about”. Additionally, both assembly theory and irruption theory resort to a kind of dualism (construction-computation and matter-mind, respectively), which throws the whole narrative of organism-environment mutualism out the window. From my perspective, this is the most fertile area to explore, and it underlies the possibility of revealing the symmetry that underwrites the perceptual abilities of organisms and the action capabilities that they support.