Relational Biology II: Towards a faithful model of life

The second chapter of this trilogy is focused on understanding what many consider to be the canonical model of relational biology, (M,R)-systems. As we will see, this model lacks an adequate biological interpretation, so it is necessary to extend Rosen's ideas to the biochemical realm if we really want to understand what life is.

Introduction

In the first part of this trilogy we studied in depth the roots of relational biology, superficially reviewing its general philosophy. Contrary to the mechanistic perspective implanted by the Newtonian paradigm, relational biology seeks to study life from the standpoint of ‘organization of relations’. In order to demystify such a conundrum, let me introduce you to what today is the canonical model of relational biology: (M, R)-systems.

In The Representation of Biological Systems from the Standpoint of the Theory of Categories, Rosen introduced category theory as a foundational tool for understanding biological organization. Unlike traditional modeling approaches that rely on state-space-based models with well-defined transition functions, category theory provides a framework for describing systems in terms of objects and morphisms—where objects represent biological entities, and morphisms encode the functional and relational dependencies among them.

Further refining these ideas, A Relational Theory of Biological Systems extended Rosen’s approach by explicitly addressing the role of metabolic and repair subsystems. Here, he developed the concept of relational closure, arguing that a truly living system must possess a structure that enables it to maintain itself through internal processes. The introduction of entailment structures in this work marked a significant step toward the formalization of (M, R)-systems, where metabolism (M) represents the transformation of substrates into useful biological components, while repair (R) ensures the system’s ability to sustain its functionality over time.

Rosen’s (M, R)-systems originated as an attempt to move beyond Newtonian state-space representations and provide a category-theoretic foundation for biological organization. His early work established a formal basis for understanding metabolism and repair as interdependent relational structures, distinguishing living systems from purely mechanistic entities. However, Rosen’s ideas were not static; over time, he became increasingly critical of traditional modeling approaches, culminating in a more radical stance that challenged the adequacy of existing scientific frameworks. Because of this and Rosen’s remarkable solitariness when writing, understanding his (M, R)-systems has become a challenge.

Building (M, R)-systems from scratch

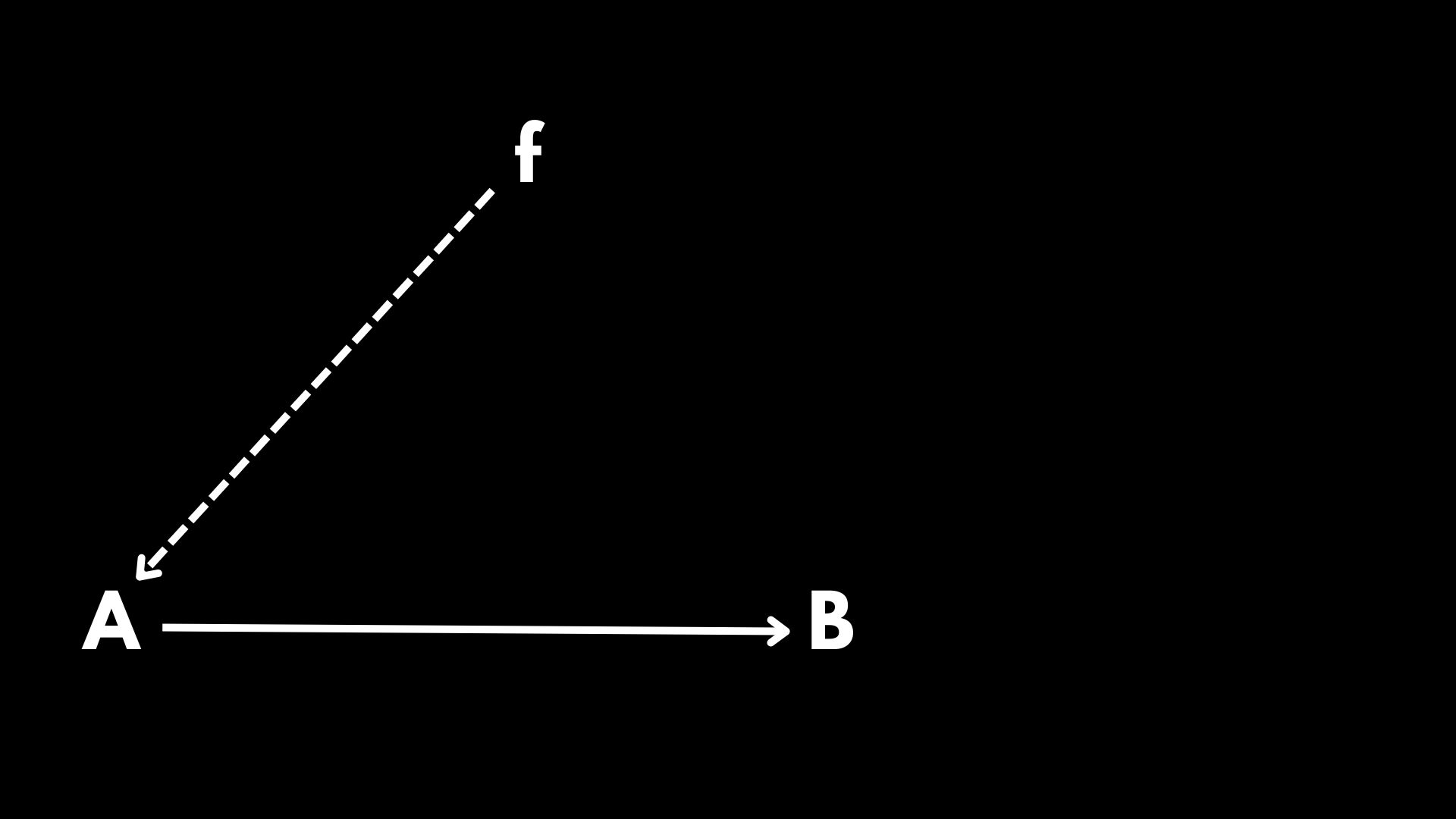

Suppose you have a functional relation, \(f(A)=B\). An alternative notation to such a functional relation is given by \(\mathcal{A}\xrightarrow{f}\mathcal{B}\). In order to explain the depth of his arguments, Rosen resorted to the following notation:

The diagram above is representing exactly our initial functional relation \(f(A)=B\), but now instead of putting the function \(f\) over the arrow, we recur to the usage of a dashed arrow pointing out to \(A\). This is telling us that when applying \(f\) to \(A\), we obtain \(B\) as a result. Furthermore, at this stage we can identify different modes of causation.

In Diagram 1 \(A\) represents material causation, which is basically the initial substrate to be transformed into \(B\). Since \(A\) is going to be transformed into \(B\), we say that \(B\) is the final causation of \(A\). However, if we want to transform \(A\) into \(B\), it is necessary the action of something promoting such a transformation. In this case such a role is assigned to \(f\), which is categorized as the efficient causation of \(A\).

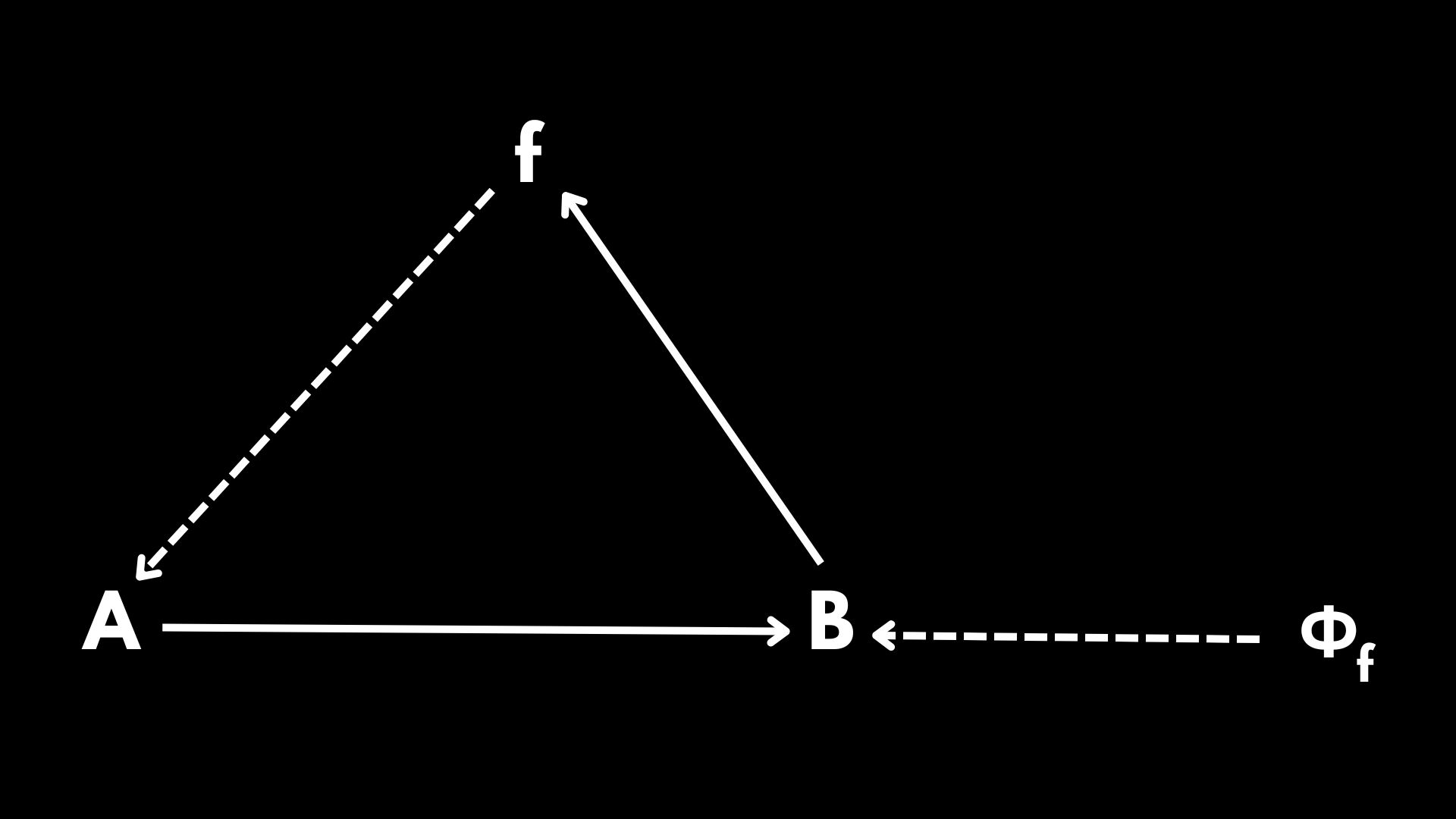

Nevertheless, observe that in this whole process, \(f(A)=B\), we are assuming that \(f\) is being provided externally, potentially by the environment or any other source. But if we want to study systems of self-organized mappings, then \(f\) should be built by the organization itself. Rosen’s solution to this problem was to invoke a new mapping \(\Phi_f\) such that when we apply it to \(B\), we obtain \(f\) as a result:

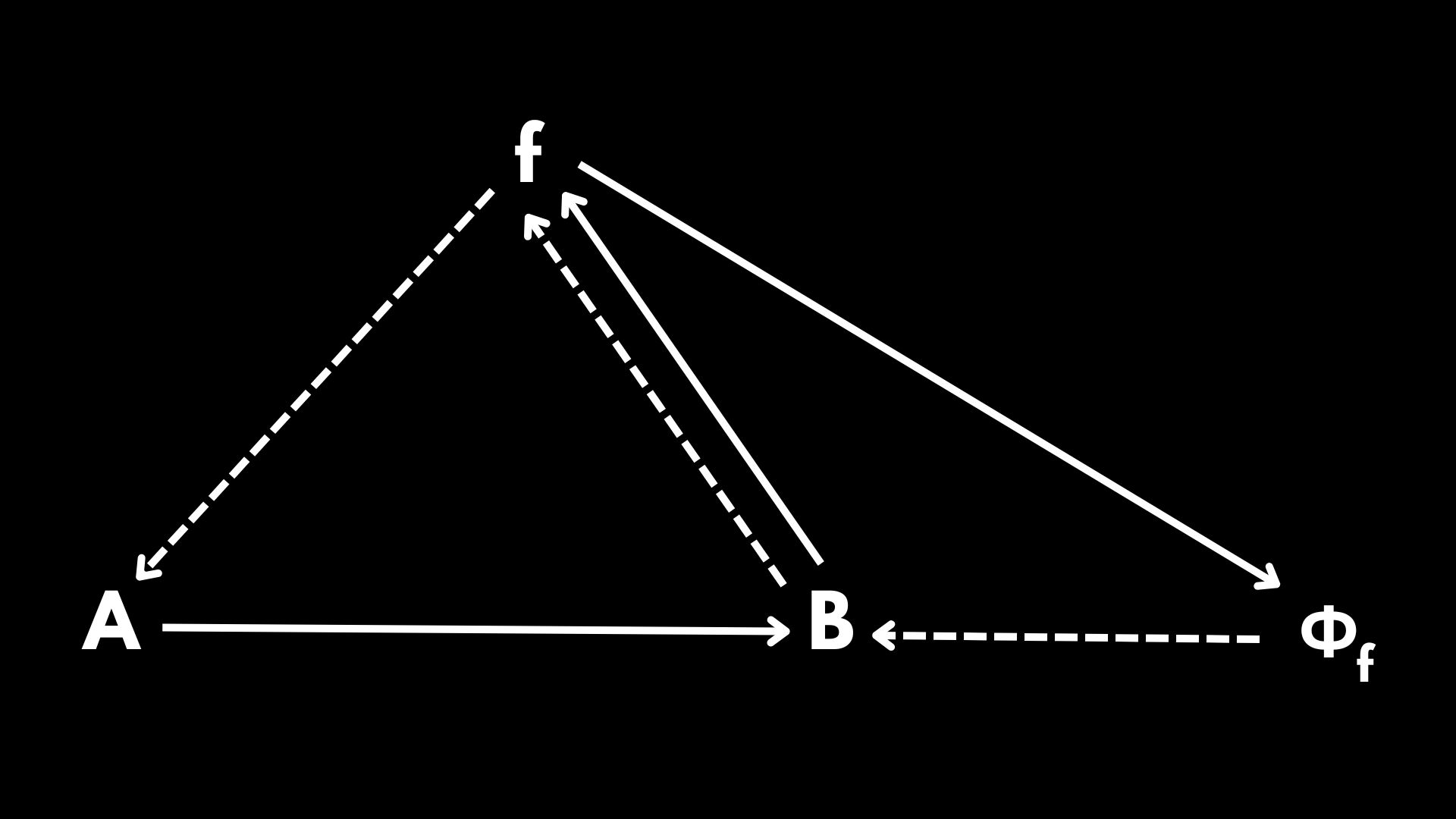

In Diagram 2 \(f\) is now being produced by the organization itself. However, \(\Phi_f\) is still external to the organization. And here comes Rosen’s leap of faith: let us assume that \(B\) has a dual role. This means that \(B\) is not only the end result of \(f(A)\), but also a function that, when applied to \(f\), produces \(\Phi_f\). Under this assumption, we recover Rosen’s famous diagram:

Diagram 3 possesses many interesting properties. First of all, Diagram 3 is open to material causation. This means that \(A\) is being provided by the environment, and biologically speaking this represents thermodynamic openness, a key property for life to exist according to Schrödinger and all his descendant line of thought.

Additionally, observe that Diagram 3 is closed to final causation. This means that all the solid arrows, which represent biological functionalities, are being provided and sustained by the organization. This eliminates any teleological interpretation of Aristotle’s four causes and it means that the autonomy we observe in living systems is a product of self-sustainability.

Last but not least, Diagram 3 is closed to efficient causation. This means that all the dashed arrows, representing all the catalytic processes within the organization, are being produced and sustained by the organization itself. And according to Rosen this was the definition of life. Life exists if and only if it is closed to efficient causation.

Now, while Rosen’s model turns out to capture properties important for life, it suffers from multiple epistemological and biological gaps. When building his (M, R)-systems, Rosen was thinking mathematically, leaving aside any biological interpretation of his diagrams. The usual approach in theoretical biology is to start with a natural system and seek to construct a model of it. Relational biology goes the opposite way: it starts with a model and seeks a realisation.

A biological alternative

Jan-Hendrik Hofmeyr’s A Biochemically-Realizable Relational Model of the Self-Manufacturing Cell presents a novel reinterpretation of Robert Rosen’s (M,R)-system, shifting from a purely abstract relational model towards a biochemical instantiation. The paper introduces the (F, A)-system—fabrication and assembly—as an alternative to Rosen’s metabolism and repair (M, R)-system, addressing the longstanding difficulties in mapping relational biological models onto real biochemical processes. Hofmeyr’s approach not only clarifies fundamental biological principles but also provides a framework for integrating key ideas from relational biology, theoretical biology, and biosemiotics.

One of the core strengths of Hofmeyr’s model is its recognition that closure to efficient causation can be achieved in multiple ways through diagrammatic representations. The (M, R)-system as originally conceived by Rosen should accomplish a type of injectivity in the hom-set of the category in order to achieve replication. Hofmeyr addresses this issue by proposing a model that explicitly separates fabrication (the synthesis of components) from assembly (the organization of these components into functional structures). This bifurcation allows for alternative interpretations of closure to efficient causation while maintaining the fundamental organizational principles of self-manufacturing systems.

Additionally, Rosen’s model reflected the one enzyme one gene hypothesis, which states that each individual gene codes for a single, specific enzyme. However, such an idea has been biologically denied. By grounding (F, A)-systems in biochemistry, Hofmeyr demonstrates that metabolic and repair processes are not merely abstract relational constructs but are physically instantiated through specific biochemical pathways. His model aligns well with contemporary understandings of cellular organization, where metabolic pathways fabricate molecular components, and chaperone-assisted self-assembly ensures their proper functional integration.

A striking feature of the (F, A)-systems is its balance between closure and openness. While it is closed to final and efficient causation, it remains open to material causation (nutrients, environmental inputs) and to freestanding formal causes (a set of instructions). This openness ensures that the system can adapt and evolve, rather than being a rigid, self-contained entity. By allowing the functional organization to shift in response to changes in its formal causes (e.g., mutations in DNA), (F, A)-systems capture a fundamental aspect of biological evolution that was not fully addressed in Rosen’s original formulation.

Conclusion

At the end of his paper, Hofmeyr situates his (F, A)-systems within a broader framework of hierarchical causal cycles. While his focus is on the cellular level, the same principles of self-maintaining context apply at higher levels of biological organization, from multicellular organisms to ecosystems and even social structures. This perspective suggests that self-manufacturing principles may have far-reaching implications beyond biology, extending into complex adaptive systems more generally.

One limitation of the current (F, A)-system model is its ‘blindness’ to the external environment. While it accounts for internal self-maintenance, it does not explicitly incorporate mechanisms for environmental sensing and response. Notwithstanding, Hofmeyr notes that this limitation can be addressed by incorporating membrane receptors and signal transduction networks into the manufacture process. Since these components are encoded in DNA, they can be naturally integrated into the (F, A)-system architecture manufacturing system. This insight highlights the importance of extending the model to capture adaptive responses, further enhancing its biological realism from a semantic point of view.

Overall, Hofmeyr’s work represents a significant advance in relational biology. By shifting from an abstract (M, R)-system to a biochemically grounded (F, A)-system, he provides a concrete framework for understanding biological self-maintenance. The model successfully integrates multiple theoretical perspectives while addressing key challenges such as multifunctionality, openness to formal causes, and evolutionary adaptation. While some refinements are needed—particularly in incorporating environmental responsiveness—(F, A)-systems provide a robust foundation for future research in theoretical biology and artificial life. Ultimately, it offers a compelling vision of how living systems sustain themselves, evolve, and persist across generational timescales.